The problem must be me

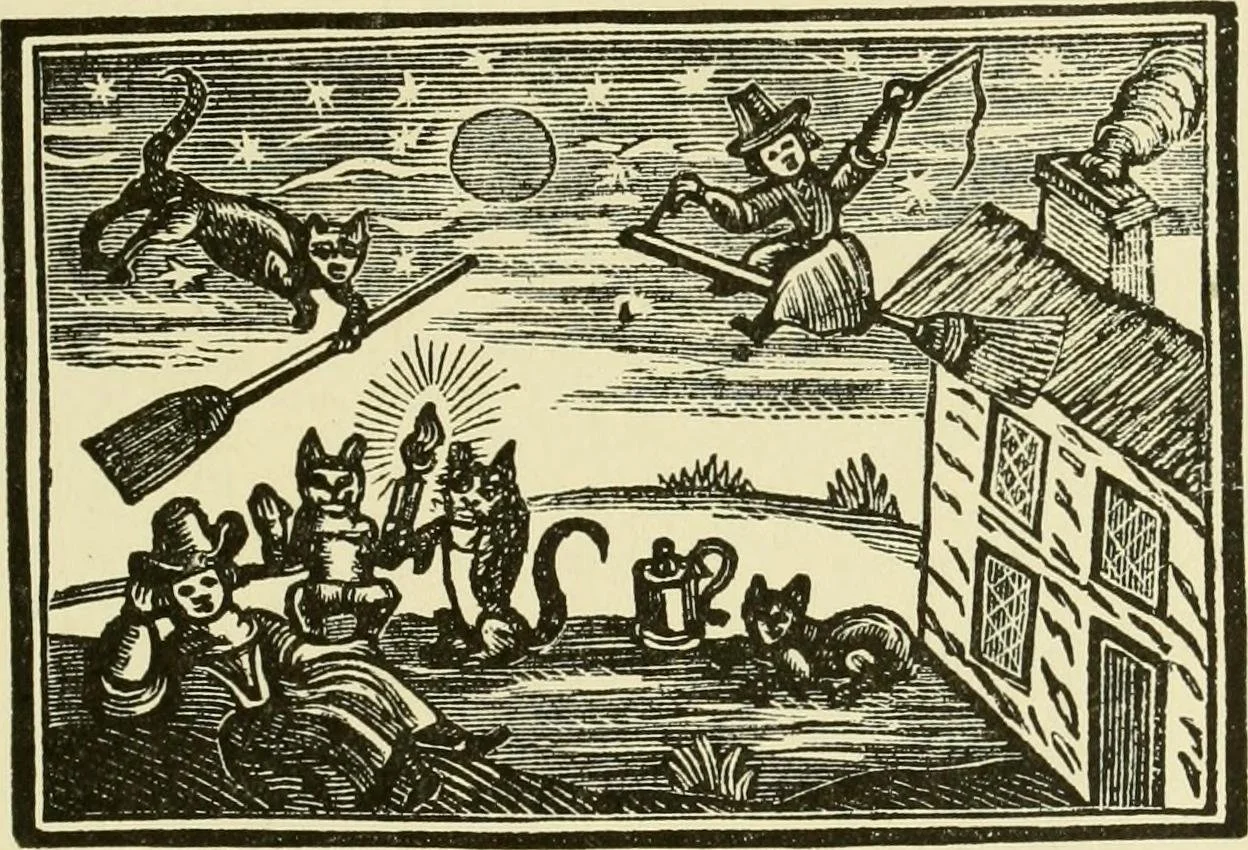

Unless you’re out riding around on a broomstick in a pointy hat and casting spells, it’s not your fault they think you’re a witch. (Image source)

I worked with a leader, Evan, who was extremely humble and self-effacing.

Evan was constantly working to improve himself. Whenever anything went wrong, his first move was to look at his own behavior. His default assumption was, “the problem must be me.”

Often, though, Evan had already done what he needed to do. He had made a plan, communicated clearly, and followed through on his promises. In my assessment, the issue was actually unrelated to Evan: The company (of which he was an employee, not an owner) was serving the wrong people. That made Evan’s job much harder.

Yes, ultimately, all of the problems you have in your life are down to you. But if your automatic position is to claim responsibility for anything that doesn’t work, you might miss important clues about what’s actually happening.

High-achieving people are usually dependable and committed. They hate to let others down, and they do whatever it takes to fix problems — sometimes, before anyone has even noticed. This type of ownership becomes such a part of a person’s identity that, without realizing it, they take on more than their fair share.

Yeah, there are those of us who need to learn commitment and follow-through. But if you’re more like Evan, maybe you need to learn the art of recognizing when something isn’t actually your fault or your responsibility. The situation may, in fact, be entirely out of your control.

How do you learn to see where your part leaves off and the other person’s begins? Well, you start with the postmortem you would always do: “I see that I should have done this and double-checked that.” You’ve discovered some tangible steps you can take to make things work out better in a similar situation next time.

But when your evaluation of the situation leads you to something more like, “I should have tried harder,” you might be crossing the line. And when the only options you can come up with involve you somehow seeing the future, predicting the unpredictable, changing the behavior of large groups of people, or using resources that you never had in the first place, you can bet that you are taking on a burden that isn’t yours to carry.

We don’t have to expect ourselves to behave perfectly in every situation. Yes, maybe you should have put your bag in the trunk, but it’s still not your fault that you were robbed. Though we can always improve, we need to have compassion for ourselves and acknowledge the limits of our power.

In tennis, I’m learning that getting the ball over the net isn’t enough. When I hit it too lightly and easily to my opponent, it’s likely to come at my doubles partner very quickly as a result. I can see that if she misses, my shot was a root cause of that. If I want to win games, I have to consider all of the factors involved in a given point.

But if my partner shows up tired or in a bad mood, that’s not something I have any control over. If the other team is two ratings higher, I didn’t cause that. And if we lose, it is counterproductive for me to believe that it’s all my fault. That doesn’t actually teach me anything about how to play the game better, just as it wouldn’t teach me anything if I blamed the loss entirely on everyone else.

Ultimately, we need to determine the truth of a situation instead of jumping to a conclusion that makes us feel comfortable. Then, the responsibility we take is real.

I once overheard a mother say to her ten-year-old child as she dropped her off, “Goodbye. I’m sorry for all of the ways I’ve failed you.” This shouldering of blame was, ironically, an abdication of parental duty (in addition to being wildly inappropriate). It was a blanket statement that meant that she was prevented from doing the hard work of looking at her own behavior.

In some cases, we might be doing the hard thing of making ourselves the martyr or the scapegoat to avoid having to do an even harder thing: to challenge someone else, hold them accountable, and stick up for ourselves.

For Evan, it is easier and more comfortable for him to say that he messed up than to call out someone else. With practice, he can learn to see circumstances more clearly. That will allow him to get even better at his job — and help other people get better, too. That’s what a leader does.