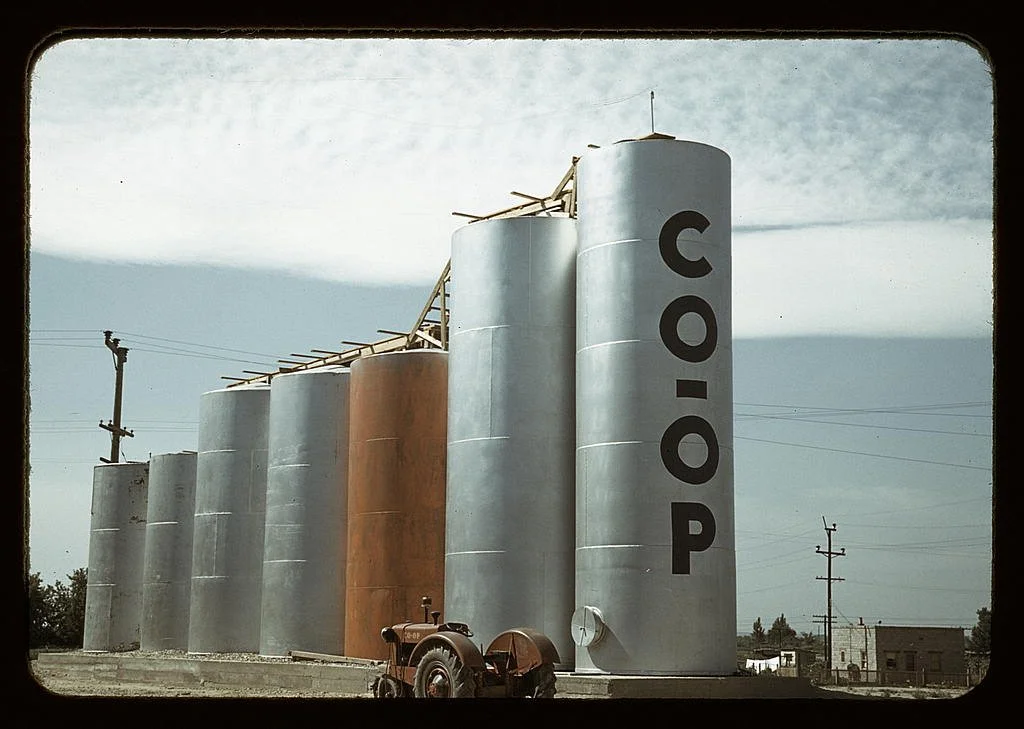

Siloing

Separate and together. (Photo by Russell Lee, Library of Congress collection)

Around 2011, I wanted to start an online business, but I didn’t know how to do it.

I had a brick-and-mortar music school, so I wondered if there was some way that I could teach music online.

Of course, there was. And if I had actually started such a business back in 2011, it would probably be a monstrous success by now.

But instead of getting into it in earnest, I waffled around. Was the name right? What format should I use for my content?

Worse, I challenged myself to figure out where this potential business fit into the landscape of other as-yet-hypothetical business ventures I was considering. There was the work I could do training music teachers, there were the music education programs I wanted to create for children, and there were the programs that I wanted to create for adults. Also, I wanted to teach piano and guitar — should I make those separate programs, or just one? And could I teach classical and pop piano on the same website or YouTube channel?

Over a decade later, just about all of these programs remain hypothetical. I wrote a few blog posts and quit. My genius approach to music education has been shared only with a select few, in person.

I can see where I went wrong, and I can see how I could move forward with one or more of these programs if I chose to.

For one thing, as I’ve discussed previously, I could build an actual plan instead of just launching wildly into the thing.

And for another, I could approach a given project with an experimental mindset, using actual data to make choices rather than trying to anticipate all possible twists and turns up front.

But there’s a third element I’d like to introduce to the discussion, and that is siloing.

Forgive me for verb-ing a noun in the obnoxious way of so much contemporary business jargon, but it expresses the concept well. Like a physical silo protects materials from the elements and prevents them from mixing with other types of materials, and a digital silo might prevent certain data from integrating with other data, I can create a business “silo” that separates a given business venture from another.

This is something people do all the time. They might have a day job and a “side hustle.” They might have a brick-and-mortar business and an online business with no crossover between the two. Or they might have two or more separate online businesses, even under different names.

Examples: A freelance web developer who also sells handmade leather products at farmer’s markets and on Etsy. A physician who also has an affiliate website related to knitting. A school janitor who moonlights as a DJ.

Such siloing is common and often necessary, but I didn’t understand that. I felt like I had to come up with some grand unified theory of how all all of my projects fit together. That’s silly. I didn’t. I just had to pick one thing and do it. But I was worried that my investment wasn’t going to pay off, so it felt scary to pursue something disconnected to what I was already doing. I thought it would be better if I somehow my existing business could benefit from this new business.

Trying to keep the new project connected to the old one weakened it because I was, in effect trying to serve two audiences at once, and trying to present myself as two different things to both of them. Messy — which was exactly what I had been trying to avoid by linking them.

Siloing is like writing under a pseudonym: The new project becomes a standalone endeavor, free to be whatever it needs to be in order to be successful. It gets to have its own offers and pricing, its own brand, its own story, and its own identity and purpose. Thus, it will have its own customers or audience who resonate with its mission. Nobody will be confused.

This is an extension of a broader principle of separating yourself from whatever you make or do. Your business is not you. That makes it a lot less fraught to launch, run, sell, close, or abandon said business. It can be an extension of who you are, but it doesn’t have to be.

Adding new projects to your life adds complexity, but trying to figure out how they are all part of an integrated whole is unnecessarily complicated. They don’t have to serve some overarching mission or be aligned with an umbrella brand. They can exist in silos, distinct and discrete, each serving a function for you and for anyone else they serve. It would have helped me to understand that a decade ago; maybe this idea can help someone else today.